An outsiders perspective on insider risk

Article

Article

Although a significant step, Professor Paul Martin, a UK national security expert, cautions that screening alone cannot fully address the complexities of the problem facing UK policing. This challenge, arising from insiders – people who betray trust – is rooted in complex human behaviour, and requires a different security response.

Wayne Couzens’ crimes exemplify insider risk. The UK National Technical Authority, the National Protective Security Authority (NPSA) defines an insider as ‘a person who exploits or has the intention to exploit their legitimate access to an organisation’s assets for unauthorised purposes’.2

Couzens exploited his role as a police officer to commit a heinous crime, resulting in devastating personal tragedy and damaging the police’s reputation—an asset crucial for its operations.

Organisations face significant security risks from insiders yet many lack an adequate understanding of insider risk and personnel security – the system of protective security measures to protect them against it, which can inadvertently foster conditions in which insiders can thrive. Martin states that physical, personnel and cyber security are hugely interdependent and should therefore be managed holistically. Insiders with authorised access can defeat most physical and cyber defences. However, many organisations have security structures that are far from holistic, with cyber and physical security managed separately while personnel security – referred to by Martin as the ‘Cinderella of protective security’ is commonly underfunded and overlooked as an HR responsibility.

Insider risk can manifest itself in many ways. Insiders steal personal data and intellectual property. They leak secrets, perpetrate fraud and sabotage infrastructure.

Some have committed acts of terrorism and physical violence, as seen in US army psychiatrist Major Nadal Hasan’s attack in 2019, the worst since 9/11 causing 13 deaths and injuring 43.3 Hasan had just been promoted and was a trusted insider. Martin highlights that while hundreds of people have been killed over the years by trusted insiders, cyber-attacks have not directly caused any fatalities.4

A commonly used term when referring to insiders is ‘a few rotten apples’. It is based on the idea that that the workforce can be split between the great majority who are entirely trustworthy and a few so-called ‘rotten apples’ who are inherently evil. Martin argues that it falsely implies that insider risk is purely the property of the individual, ignoring the crucial influence of work and home environments, along with other external factors, in shaping an individual’s tendency to commit insider acts. Research suggests workplace experiences such as job demands and interactions with

managers and colleagues play a significant role in developing insider intentions.5

Furthermore, it appears that most harmful insiders turn rogue during their time in the workplace, rather than joining with malicious intent. A 2013 study revealed just 6% of insider incidents were deliberate infiltrations6, indicating insider behaviours and intentions typically develop gradually.

The best detectors of insider risk are the workforce itself. Martin emphasises the critical need to cultivate environments where there is a high level of trust between employees, the organisation, and stakeholders. High trust correlates with reduced insider risk7, and such organisations are often more innovative, agile, and better equipped to handle change. They’re also more inclined towards openness, collaboration, and risk-taking.

Trust must also extend to the organisation’s reporting mechanisms, like hotlines and ‘speak up’ channels. If the workforce lacks trust in these systems, they won’t use them to report suspicious behaviour. It’s crucial that employees believe the information they provide will be handled sensitively and lead to appropriate actions without negative repercussions.

Yet Martin warns against complacency, “A high-trust organisation doesn’t mean assuming that everyone is trustworthy.” He highlights a common thread in insider incidents is the failure to act on early warning signs such as the case of Hasan8 who displayed multiple red flags such as openly supporting extremist beliefs and sending alarming emails about martyrdom which were overlooked. The Hasan incident underscores the critical need for prompt action in response to potential threats.

The best personnel security systems excel at identifying the subtle, early indicators of potential insider risks, preventing them from escalating into full blown insider behaviour. According to Martin, one way of doing this is through a compassionate aftercare welfare approach, in which the organisation seeks to help individuals with whatever problems might be nudging them onto the developmental path towards insider action.9 The welfare approach recognises most people are not going to turn into harmful insiders. An organization that actively provides support and fosters a caring culture is often able to address and resolve potential issues early on10.

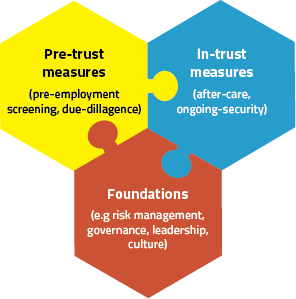

Organisations often want a silver bullet to manage insider risk yet Martin points out that no single technology can fully safeguard against it. Popular strategies like automated monitoring software for detecting forbidden activities on IT systems or pre-employment screening processes are limited as they fail to address the fact that most incidents happen after hiring. Furthermore, cases like Couzens and serial rapist police officer, David Carrick, show that risks can occur beyond the workplace. Therefore, relying on compliance processes might only treat the symptoms, not prevent the risks. Martin emphasises, “Personnel security requires an-depth defence system of complementary measures. The fundamental reason is that insider risk is an emergent property of a complex adaptive system. Systems problems require systems solutions, not silver bullets.”

Research indicates that within the Big Five Personality traits, low levels of Agreeableness and Extraversion are associated with heightened insider risk.12 Additionally, among the Dark Triad personality traits13, narcissism is particularly predictive of insider risk.14 Narcissists are typically prone to intense anger and are more likely to seek revenge when provoked. Mental health issues also contribute to risk in certain instances.

The ongoing trustworthiness of individuals should also be assessed. The four key components of trustworthiness are as follows15:

By carefully considering these factors, organisations can make informed strategic decisions that safeguard their interests and foster a trustworthy work environment. Ultimately, people are both the source and bearers of security risk which highlights the critical need for ongoing vigilance within organisations to reduce insider risks and build resilient, high-performing work cultures.

As Paul notes, trust is an organisation’s most valuable asset. No organisation is safe unless it can trust its people.

Professor Paul Martin is Professor of Practice at Coventry University’s new London based Protective Security Lab, Security Practitioner with more than 30 years’ experience in the UK national security arena and the author of Insider Risk and Personnel security published in 2024.